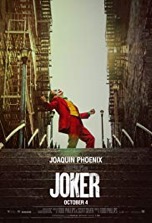

Joker (R)

23/11/19 23:30 Filed in: 2019

Starring: Joaquin Phoenix

October 2019

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. Views are my own and elaborate on comments that were originally tweeted in real time from the back row of a movie theater @BackRoweReviews. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

If somebody said “Joker” in the 60s, the name Cesar Romero (from the Batman TV show) would immediately come to mind. In the 80s, the Clown Prince of Crime received a sinister facelift from Jack Nicholson (in Tim Burton’s Batman movie). In the 90s, Joker was brilliantly voiced by Mark Hamill (in Batman: The Animated Series).

Of course, since 2008, the name Joker has become synonymous with Heath Ledger’s mesmerizing portrayal of the anarchic antagonist in The Dark Knight (yes, Jared Leto played Joker in 2016s Suicide Squad, but his take on the madcap villain had neither the cultural relevance nor the staying power of Ledger’s). Even though it’s been over a decade since TDK captivated audiences worldwide, Ledger’s Academy Award-winning performance still looms large in people’s minds. In fact, many still struggle with accepting any other actor in the role.

But if anyone could pull off Joker, it would be Joaquin Phoenix…and he does, to a superlative degree. With all due deference to director Todd Phillips (The Hangover) and the army of artisans who crafted this astounding cinematic achievement, what would Joker be without Phoenix? His performance is the very definition of what it means to chew scenery (in the positive sense). I could gush about Phoenix’ refinement as an artist ad nauseam, as every other reviewer will from here to Arkham, but there are many other worthy aspects of the film to assess as well.

Just as Phoenix’ acting choices will be analyzed by fans and film students for years to come, so too will the movie’s directing, cinematography (Lawrence Sher), and story (Phillips and Scott Silver). The film evokes the gritty NYC milieu of Martin Scorsese’s 1976 masterwork, Taxi Driver, which starred Robert De Niro (who co-stars here as Murray Franklin, a Johnny Carson style late-night TV host) as Travis Bickle, a mentally ill working stiff who tries to assassinate a political candidate.

If there’s a knock on Joker, it’s lack of originality. Not only does Joker hearken back to Driver, it also wholesale borrows its premise from Scorsese’s The King of Comedy (1982), which starred De Niro as wannabe stand-up comic Rupert Pupkin. Pupkin is unemployed, lives with his mother, fantasizes about becoming famous, commits criminal acts and appears on a late-night show. Joker’s Arthur Fleck (Phoenix) has a similar journey, but whereas Pupkin’s mother always yells at him from off-screen, we actually get to see Fleck’s mother, Penny (Frances Conroy).

Penny claims to have had an affair with Thomas Wayne (Brett Cullen) in the past, which, in Fleck’s mind, makes him the son of a multimillionaire. Fleck visits Wayne Manor in an attempt at cutting in on his perceived inheritance and meets a young Bruce Wayne (Dante Pereira-Olson). This is the closest the film comes to the world of the comic book. Thankfully, the movie contains no characters with capes, cowls or names that begin with Bat or Cat.

If the film loses points for being derivative, it makes them up (in spades) with execution. The cast is solid from top to bottom and boasts some truly fine talent in tailor-made roles. Shea Whigham and Bill Camp shine as hard-boiled detectives who smell a rat with Fleck. Zazie Beetz is also perfectly cast as Fleck’s love interest—a kindred spirit who brings a measure of sweetness to his otherwise bitter life.

Joker would’ve fallen flat (like Pupkin’s comedy act) had it failed to engender sympathy for Fleck, whose uncontrollable fits of laughter are based on a real condition called Pseudobulbar affect (PBA). Due to these often untimely outbursts, Fleck is taunted, bullied and beaten. Although this inhumane treatment doesn’t forgive the heinous acts Fleck commits later in the film, it does produce pathos in the viewer and adds to the character’s complexity.

Phillips does an exceptional job of creating atmosphere in the film (although I wish he would’ve held his establishing shots a few seconds longer…to let them breathe a bit). The movie’s showcase sequence, where Joker dances his way down several flights of stairs, is exquisitely lensed and choreographed (and acted). The scene takes place 3/4ths of the way through the movie and marks a defining moment for the character. Even though it may seem like a strange comparison, those same criteria apply to the iconic scene in Rocky when Rocky Balboa (Sylvester Stallone) runs up the steps to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. However, the sequences are polar opposites both directionally and thematically (Joker’s giddy descent into evil is contrasted by Rocky’s arduous ascent to glory). Coincidentally, both characters have a five letter name. Curiously, Joker was inspired by Driver, which was released the same year as Rocky (1976).

In selected scenes, Phillips employs a filming technique that’s been used throughout motion picture history—particularly during the film noir period—where the camera frames a character through bars, window panes, chicken wire, grates, etc. Symbolically, this conveys that the character is trapped in some way, or is destined to be incarcerated. Cannily, whenever Phillips shoots his main character through wire glass (records room at the hospital) or metal bars (the front gate of Wayne Manor), Fleck is always on the outside where he’s able to walk or run away to maintain his freedom. When Fleck is finally captured and tossed into the back seat of a police cruiser, we expect the payoff of these visual cues to be Joker in jail. But Phillips shatters our expectations of Joker’s fate with a twist ending.

That controversial coda presents an interesting theory: what if the Joker in Joker isn’t our Joker (the one we know from comic books and other DC TV series/movies)? What if he’s merely a type of Joker, like the many people who wear clown masks and riot against the police near the end of the movie (such images recall the army of citizens taking to the streets wearing Guy Fawkes masks in V for Vendetta)?

Evidence to support this theory: 1. Arthur doesn’t kill the Wayne’s (admittedly, this is a weaker point since Joker isn’t always the perpetrator of the Wayne murders in the various versions of the Crime Alley vignette). 2. The name Arthur has never been one of Joker’s aliases (Jack or Joe are the most common). 3. There’s an age disparity in the film: Pereira-Olson is 9, Phoenix is 44. If the character’s ages are the same as the actor’s, Joker is 35 years older than Batman. That means by the time Bruce returns to Gotham (after training abroad) to take up the mantle of Batman, Joker would be headed toward retirement. That math doesn’t jibe with all other versions of the Batman/Joker mythos. Regardless of whether this theory holds water, only a psychological thriller this rich with meaning and nuance could produce such a mind-bending possibility in the waning seconds of the film.

In the final analysis, Joker is a masterfully macabre origin story of one of the most colorful and enduringly popular villains in all of fandom. Peerless directing and acting mark this frightening portrait of psychological derangement.

Joker is the least cartoony, most artistic comic book film ever made. Despite the jocularity of its lead character and its moments of black comedy (the hilarious “punch out” scene), Joker is a serious film about serious issues (cynicism, mental illness, class inequality, and the rise of anarchy). Due to its uber-graphic slaughter scenes, Joker is also the most mature superhero (or supervillain) movie ever made.

The sad reality is that the film will probably inspire mentally ill members of our society to attempt acts of violence similar to the ones portrayed in the movie. It’s also profoundly tragic that such little progress (socially and in the field of mental health) has been made in the intervening years between Driver and Joker.

The movie’s ending leaves things open to interpretation. It also leaves things open for a sequel. Unless it’s destined to become a landmark film like The Godfather Part II (1974), I say leave this modern masterpiece well enough alone.

I’m not joking.

Rating: 3 1/2 out of 4