2024

Homestead (PG-13)

25/01/25 01:19

Starring: Neal McDonough

December 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

The film opens with a doomsday scenario—a nuclear bomb is detonated just off the coast of Los Angeles. The aftermath plays out in a series of taut, well executed vignettes as characters scramble to get out of the city, which is blanketed by a dense layer of noxious, rust-hued air that’s just a few shades darker than the typical rush hour smog.

The next phase of the film brings us to the Rocky Mountains and a large estate owned by Ian Ross (Neal McDonough). We’re introduced to Ian’s family and a group of ex-military hoorahs, led by Jeff Eriksson (Bailey Chase), Ian has hired to guard his property. When food, water and supplies run out in the town below, the homeless and hungry amass at Ian’s main gate, hoping for a handout or an opportune moment to storm the gate (as does a SWAT team during the movie’s climax). Aside from security challenges, one of the most pressing problems, with winter approaching, becomes how to feed and shelter a growing number of people.

Homestead comes to us courtesy of the crowd-sourced Angel Studios (The Chosen), and is essentially a 2-hour pilot for a future web series. The early stages of the film are really good and feel like a legitimate big-screen release. However, when the action shifts to the titular locale, the movie begins to feel more and more like a CW TV series. Other dead giveaways that Homestead isn’t up to the standard of a major studio film is the music by Benjamin Backus. In addition to aggressive underscoring during conversations to heighten the drama, the music was mixed for the small screen rather than the big screen. What gives this away? There are several instances where the music is too loud, drowning out dialog, including several key voice-over narrations near the end of the film.

Despite its technical shortcomings, Homestead is a unique vision of a post-apocalyptic America. Told from a conservative POV, the story foregrounds the complex issue of isolationism vs amnesty for all in survival situations. Ian’s front gate and property lines are an analog for the U.S./Mexico border. Ian’s wife, Jenna (Dawn Olivieri), urges her husband to invite the refugees inside their expansive property, but abacus-bound Ian refuses, stating they barely have enough to sustain their own family and hired security men.

But when Ian is sidelined by a stray bullet, Jenna completely disregards his wishes and admits everyone camped out at the front gate. In a predictable twist, the skills and knowledge possessed by the newcomers helps solve many of the problems Ian has been stressing over. This compassionate, liberal action provides a solution to the immediate problems facing the homestead, and provides a happy resolution for the movie.

As the series progresses, my major request is that the producers/writers make Ian more heroic and less of a stick in the mud. McDonough is a terrific actor, but his character here is downright annoying at times. He frets over everything and doesn’t seem to have the faintest modicum of faith, which is ironic since this is supposedly a faith-based film (it’s actually a faith-lite film).

Though Ian clearly constructed his estate with the apocalypse in mind, he seems ill-equipped to deal with the challenges that arise during the film, which is uber frustrating. He’s indecisive, uninformed and eternally pessimistic. He’s also cold. We rarely see him provide emotional support for his wife or daughter. Ian’s pride in the abilities of his own people to defend the compound is woefully unfounded, as a war games scenario with the new security forces makes abundantly clear.

Ian’s inability to make sound decisions creates a strange power dynamic in the film. As the de facto main character, Ian should be the protagonist, but due to his weak leadership, Jeff’s supreme competence and Jenna’s moral convictions make them the real power brokers in the movie.

Angel Studios, please make Ian the true leader of the series. Also, make him the emotional and spiritual leader of his family and those under his care. Accomplishing that will make Homestead feel more like home.

Note: While putting the finishing touches on this piece, I learned that McDonough will not appear in the series. This type of bait-and-switch gimmick, employed to increase viewership, is distasteful and disingenuous. A similar casting ploy was used for TV’s Invasion, which billed Sam Neill as its main star. Annoyingly, Neill only appeared for a few minutes in the first episode. This is a devilish move from the purportedly seraphic studio.

Rating: 2 ½ out of 4

The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim (PG-13)

24/01/25 00:48

Starring: Brian Cox

December 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

Set nearly 200 years before J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings books, The Lord of the Rings: The War of the Rohirrim is an animated adventure helmed by journeyman anime director Kenji Kamiyama. This foray into Middle-Earth focuses on the King of Rohan, Helm Hammerhand (voiced by Brian Cox), and his family, who fight to defend their realm against an army of bloodthirsty avengers known as the Dunlendings.

The story—written by Jeffrey Addiss, Will Matthews and Philippa Boyens—is based on narrative elements found in the appendices of The Return of the King, the final book in Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Other than brief run-ins with a handful of fantasy creatures that later appear in Peter Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings movies, the bulk of the story involves warring human (humanoid?) tribes, whose petty and violent actions completely justify Elrond’s pessimistic appraisal of men in The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring (2001): “scattered, divided, leaderless.” The largely human-centric, magic-free story makes Rohirrim a unique chapter in the Middle-Earth saga.

Though the animation in Rohirrim is consistently superb, the hand-drawn characters tend to clash against the near-photorealistic landscapes. Many familiar locations from the Rings movies appear here, including Edoras, Isengard and Helm’s Deep. All are finely-rendered and may produce feelings of nostalgia for fans of Jackson’s Rings films.

While its efforts to transform young ingenue, Hera (Gaia Wise), into an action hero (a la the younger Galadriel in The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power) are overdetermined, the story, on balance, is quite good. Rohirrim is a reverent attempt at portraying the fantasy, characters, trappings and tropes Tolkien first created in The Hobbit (1937).

Though fairly appropriate for kids, the movie doesn’t cater to them. To its credit, the film doesn’t employ a Disney-style sidekick to infuse the story with comic relief. To its detriment, the film is serious to the point of being dire. An animated movie need not be kiddie, but shouldn’t it at least be a little fun? Rohirrim is devoid of anything that even hints at levity and, from all indications, its characters are allergic to humor.

The film’s strong suit is its well-executed action sequences. Powerful and perfectly paced, without becoming protracted, the movie’s action beats help move the story forward without dominating it or detracting from it. Though decidedly violent, the action scenes here are surprisingly less bloody than those in the earlier animated The Lord of the Rings (1978).

Composer Stephen Gallagher turns in an excellent score for Rohirrim, which briefly employs Howard Shore’s main theme and The Riders of Rohan motif from the Rings films. While capturing the essence of Shore’s work, Gallagher creates a wholly original, dynamic and effecting sound tapestry.

Though far less goofy than the animated movies produced in the late 70s and early 80s based on Tolkien’s works, Rohirrim lacks the charm, whimsy and magic of those other animated efforts. Still, Rohirrim serves as a quality prequel to The Lord of the Rings trilogy, and is a worthy entry into the Middle-Earth mythos.

Will this film earn enough money to justify a sequel? Time will tell. But for the moment, Middle-Earth is at peace.

Rating: 3 out of 4

Bonhoeffer: Pastor. Spy. Assassin. (PG-13)

08/01/25 22:41

Starring: Jonas Dassler

November 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

Based on the true story of author, musician, pastor and spy, Dietrich Bonhoeffer (Jonas Dassler), Bonhoeffer is a predominately somber biopic that begins during the titular character’s childhood and ends with his tragic death—2 weeks before the end of WWII.

By now, it’s been well established that the German military, body politic and even general population were complicit in supporting and facilitating Hitler’s rise to power. Lesser known is the German church’s full-throated support of the Chancellor in pulpits from Berlin to the hinterlands.

Upon hearing a priest publicly elevate Hitler to the status of Christ, Bonhoeffer became incensed; his scathing criticism of such blasphemous speech dared to call out high ranking clergy members for their heretical espousal. Bonhoeffer’s divisive words effectively split the church along ideological lines—and put a bull’s-eye on his back by both pro-Hitler sympathizers and the dreaded Gestapo.

According to the movie, kid Bonhoeffer had an uncanny ability to evade capture in games like hide-and-seek. Ironically, when presented with an opportunity to escape from prison, adult Bonhoeffer chose to stay and face certain death rather than fleeing and taking a chance at life. This decision was proof positive that Bonhoeffer trusted God’s plan more than his own abilities…and his own life. Indeed, it would’ve been much safer to stay in America and simply wait out the war. But Bonhoeffer submitted himself to God’s will, essentially saying what Christ did at Gethsemane, “Not my will, but thy will be done.”

One of the subplots involves a failed assassination attempt of Hitler, who sniffs out the plot and arrogantly tells the would-be killer he lacks courage. Historians tell us that Hitler saw each failed attempt on his life as further evidence that he was doing God’s work. This demonstrates just how easy it is for someone to deceive themself, and others, with lies that sound so much like the truth, the error of their way may not be revealed until 6 million people have been exterminated. Though the phrase is often employed from a positive or aspirational perspective, this is the true “human condition.”

In spite of its slow pacing, Bonhoeffer is a well-produced period piece that tells a familiar story (the ascendency of Hitler) from a unique angle (the ecumenical embrace of evil). It contains a compelling character study of a deeply concerned citizen who sounded the alarm, a la Paul Revere, to warn his countrymen of the impending dangers of fascism and the Nazi movement.

Bonhoeffer possessed unwavering conviction and courage during one of the darkest periods in human history. With the resurgence of socialism around the globe and even in the American government, we could certainly use more people of high moral character—like Bonhoeffer—in the world today.

A sobering reminder of the atrocities of the past, Bonhoeffer challenges us to remain vigilant in an increasingly evil age.

One thing’s for sure; I’ll never look at strawberries that same way again.

Rating: 2 ½ out of 4

Here (PG-13)

26/11/24 20:41

Starring: Tom Hanks

November 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

The movie opens during the prehistoric age with volcanoes belching lava and a pack of dinosaurs pursuing their prey. After the dust from an asteroid crash causes an ice age, we’re brought forward in time to when indigenous people settled the forested region we now call North America. But then, quicker than you can say “Mayflower,” the forest is cleared and a large estate is erected during America’s colonial period.

Years later, a humble home is built across the street from the mansion, and that abode becomes the locus of action for the rest of the movie. The main storyline picks up after WWII when returning soldier, Al Young (Paul Bettany), and his young wife, Rose (Kelly Reilly), move into the house. When Al and Rose’s adult son Richard (Tom Hanks) marries Margaret (Robin Wright), the newlyweds move into their house to save money.

With the exception of a few minor events that transpire in other time periods, the balance of the movie focuses on the Young family during several decades of their lives together.

This film comes to us courtesy of some of the top names in Hollywood. Here is directed by Robert Zemeckis of Back to the Future, Contact and Cast Away fame. In the leading roles are Hanks and Wright, who also starred in the director’s smash hit, Forrest Gump. Another frequent contributor to many of Zemeckis’ films is composer Alan Silvestri, who delivers a tender, deeply-affecting score here that rivals his best work. The screenplay was written by Zemeckis and Eric Roth, based on the 2014 graphic novel of the same name by Richard McGuire.

Here tells an unusual story of the many lives that inhabit the same physical space (plot of land and the house built on it) over the course of many centuries. As outlined in the synopsis, this multigenerational story begins during prehistoric times and ends in present day America. Though it boasts an undeniably novel concept—that seems better suited to a sci-fi epic than an intimate family drama—will the movie’s constant jumping between timelines confuse or exhaust its audience?

The visual cue that lets us know when we’re transitioning from one era to another is a simple rectangle, which can vary in size and appear at random places on the screen. A different timeline coalesces inside the new rectangle and, after an indeterminate interval, the shape expands to fill the entire screen, replacing the previous scene. In this way, these window panes serve as time portals through which we visit the many historical periods featured in the story. Since it’s used throughout the nearly 2-hour movie, will this visual device become tedious for the audience?

Also, since most of the story takes place in the same room (and is shot in the same direction), the bulk of the claustrophobic film comes off like a glorified stage play. Plus, will those who watched the trailer, which mostly focuses on the Young family and sells the movie as a straightforward drama, feel cheated by the sprawling story replete with period-hopping crosscutting?

Another questionable creative choice is the use of de-aging software (in this case, a new AI tool called Metaphysic Live was employed) on some of the key actors. This technology works well enough in dimly-lit interiors and in medium shots, but is less convincing in close-ups. I’m no FX expert, but in observing mocap or deep fake shots (especially of well-known actors) in TV series and films, a la Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, it seems like these CGI shots grow more conspicuously fake as time passes.

But all is not lost, the movie’s acting is stellar…in any time period. Though Bettany and Reilly play second fiddle to Hanks and Wright, they turn in excellent performances; Bettany’s portrayal of the hard-of-hearing, shell-shocked Al is finely attenuated. Also impressive, in a meager role, is Michelle Dockery, who plays the fretting wife of an airplane pilot in the early 1900s.

Of course, I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the other generation-spanning film Hanks starred in, Cloud Atlas. Fortunately, Here has little in common with that jumbled mess of celluloid. That’s all I have to say about that.

It’s been observed that Zemeckis has a penchant for foregrounding existentialism in his films. This can be observed in the way a feather randomly floats on the wind in a handful of scenes in Forrest Gump and in the circuitous journey of the lost train ticket in The Polar Express. In Here, the existential symbol is a hummingbird that flits in and out of several scenes.

So, what are the key takeaways from Here? The film centers on several meaningful aspects of life including family, legacy, memories, and major events such as marriage, the birth of a child, and the loss of a parent.

One of the main themes in the movie is the fleeting nature of life; Richard frequently makes statements like, “time sure does fly.” This is a sobering reminder of the brevity of life and that it’s vital to make the most of every opportunity. Watching the generations fly by can serve to remind us of our own mortality and cause us to consider what we’re passing on to the next generation.

Some of the characters live with regret that they never got a chance to pursue their dreams (Richard wanted to be a painter, Rose wanted to be an accountant, and Margaret wanted her own house), because they had to make money and raise a family. One of the hardest things to accept is when the plans we have for our life don’t work out.

It’s ironic that when Margaret is a young mother, she hates Richard’s parent’s house, yet at the end of the movie she says she loves it; not because of the physical space, but because of the people that inhabited it and the wonderful memories they made together. This is a poignant principle: a house is just a structure, it’s the people that make it a home.

Another topic the film briefly touches on is worry. For years, Richard thought worrying would keep painful things from happening to him and his family. Later, he admits to Margaret that existing in a perpetual state of worry prevented him from really living.

Richard’s excessive worrying and refusal to move out of his parent’s house causes a rift in his marriage. Eventually, Richard and Margaret part ways. It’s unclear whether the couple is separated or divorced. Also unclear is if they ever reconcile their relationship by the end of the story. At the very least, they seem to be friends again, which paves the way for a happy ending.

Here is a decent drama delivered by some of Hollywood’s finest talent, both in front of and behind the camera.

Though it has many moving moments (like the montage depicting Al’s passing or the final scene when Margaret remembers finding her daughter’s blue ribbon in the couch) the movie, as a tapestry of disparate plot threads, isn’t nearly as beautiful or indelible as it could’ve been. The major detractor here is the underdeveloped sidebar stories. Excising these extraneous elements could’ve produced a stronger story about the Young family; more time spent on the ancillary kids and grandkids may have forged a deeper empathy for the entire family, which could’ve created a richer cinematic experience.

In the end, Here is an ambitious effort that capitalizes on superb directing and acting and frequently hits the nostalgia button with its period-appropriate clothes, cars and interior decorations, but ultimately falls short of being a cinematic achievement.

If you’re looking for something a little less scattershot and a little more substantive, you might have better luck at the neighbor’s house…‘cause you definitely won’t find it here.

Rating: 2 out of 4

The Wild Robot (PG)

30/10/24 21:34

Starring: Lupita Nyong'o

September 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

In some far-flung forest, frolicking animals accidentally activate a robot inside a busted crate. Following its programming, the robot, Rozzum unit 7134 (voiced by Lupita Nyong’o), tries to assist the skittish animals, but ends up doing more harm than good in many instances. In a fateful moment, Roz falls onto a bird’s nest, killing the mother and crushing all but one of the eggs.

Roz’ mission becomes protecting the egg at all costs, especially from a wily fox named Fink (Pedro Pascal) who fancies the egg as his next meal. As if fending off ferocious beasts isn’t enough of a challenge, Roz’ task gets far more complicated when the egg hatches, revealing an adorable little chick that follows the robot around as if the mechanical being is its mother. Reprogramming itself to learn how the various creatures communicate, Roz seeks advice on how to deal with this “crushing obligation” from a possum mother, who simply recommends patience.

But how can a robot programmed to serve a human family raise a tiny gosling on a hostile island where everything wants to eat it?

Welcome to the wondrous world of The Wild Robot.

Based on the book of the same name by Peter Brown, The Wild Robot is directed by Chris Sanders (How to Train Your Dragon) and produced by DreamWorks Animation and Universal Pictures. The final animated movie to be produced entirely in-house by DreamWorks, The Wild Robot is a real gem. Visualized in a similar style to Hayao Miyazaki’s celebrated animated features, The Wild Robot has a gorgeous, painterly aesthetic that gives it a dreamy, fairy tale quality.

The movie boasts several magical sequences, like when Roz touches a butterfly-blanketed tree and the myriad insects explode into a swarm of color and scintillating beauty, or when Roz teaches young Brightbill (Kit Connor) how to fly down a leaf-covered stonework runway, or when Roz holds onto a tree with one arm and leans out over the edge of a cliff to watch the migrating geese fly away into the sunset. In contrast to these “big moment” sequences, even the movie’s quiet passages are deeply affecting, like the shot of a melancholy Roz sitting in the forest as snow gently falls to the ground. The “story time” sequence, which is animated in a different style than the rest of the movie, is sheer genius. In short, the lovingly crafted and brilliantly realized animation in this film creates an alluring, immersive and unforgettable visual experience that favors traditional, handcrafted animation over the pristine, photorealistic CGI of most modern animated features.

As with the assorted forest animals, the movie’s cast is equally diverse. In addition to Nyong’o, Pascal and Connor, many notable stars lend their voice talents to the film, including: Bill Nighy as elder goose and migration leader Longneck, Ving Rhames as the falcon Thunderbolt, Mark Hamill as the bear Thorn and Catherine O’Hara as the possum mother Pinktail.

Spoiler alert: Though populated with colorful characters and buttressed by an engaging and moving story, there’s very little that’s new here. The “swapping sympathies” plot—where an individual from a more advanced society falls in with the natives, identifies with them, and defends them against aggressive members of their own race—has been employed in many movies, including: Enemy Mine (1985), Dances with Wolves (1990) and Avatar (2009).

Also, there’s an oblique reference to Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer (song and 1964 TV special) in the movie. When Brightbill is first reunited with the other members of his species, they call him names and ostracize him. Later, when the geese come under attack by robots, Longneck places Brightbill in charge of leading the birds to safety. When the geese arrive back home, they praise Brightbill for his leadership and courage under fire. Like Rudolph, Brightbill goes from outcast to hero (a similar redemptive story arc is also present in Happy Feet).

Allusions aside, the story (adapted by Sanders from Brown’s book) contains several adult topics that add a deeper dimension to the film. This isn’t the first story to depict a robot walking through nature, but that visual foregrounds the impact of technology (specifically AI) on nature. Can technology and nature peacefully coexist, as the movie suggests? Time will tell.

Another fascinating subplot involves predetermined responses vs free will. In a desperate attempt at dealing with the complexities of parenting, Roz alters its programming. This decision gives Roz the capacity to feel, and eventually love. But when Roz encounters another of its kind, the other robot determines that by altering its programming, Roz has become defective. This is an ironic viewpoint since the capacity to override our programming (learn and grow) is what makes us human…and makes life worth living.

Yet another of the movie’s many themes is isolationism vs social integration (the animals are only able to defeat the invaders when they work together). But isn’t this topic a tad advanced (and uninteresting) for most kids? And, is this just an innocuous subplot or a thinly-veiled attempt at indoctrinating our children with a pernicious form of idealism (wolves and bears don’t pal around in the real world)? Hollywood’s track record on such matters would point toward the latter.

For a kids’ movie, The Wild Robot contains an inordinate number of references to death. Indeed, the dialog is saturated with words like “dead/die/dying,” “expire,” “kill/killed,” “murder,” “terminated,” and other morbid terms like “squish you into jelly.” Alarmingly, much of this fatalistic dialog comes from young characters.

It’s unclear why such dire dialog is infused into this ostensibly family film. Perhaps it’s Sanders’ way of underscoring the predatory, “survival of the fittest” aspect of life in the great outdoors. But is an animated film the appropriate place for this macabre topic?

Despite minor quibbles over the appropriateness of its speech and subject matter, The Wild Robot should appeal to a wide audience, including kids and adults who enjoy well-told, finely-rendered animated movies. It joins the small set of stellar robot animated flicks, which represent some of the finest animated features ever made: The Iron Giant (1999), WALL-E (2008) and Big Hero 6 (2014). Regardless of where it ranks, The Wild Robot justly deserves to be placed alongside these other animated greats.

The movie’s coda sets up the possibility for another story with these lovable characters. But whether or not a sequel is ever produced, by DreamWorks or some other animation studio, this movie is a wild ride worth taking.

Rating: 3 out of 4

Reagan (PG-13)

25/09/24 22:46

Starring: Dennis Quaid

August 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

March 30, 1981 – Washington, D.C.

Ronald Reagan (Dennis Quaid) wraps up his speech at an AFL-CIO meeting with an amusing anecdote about baseball and diapers. Though the sky is gray, the mood is light as Reagan shares a joke with several staffers on the way to the motorcade. He approaches the open door of the presidential limo. Shots ring out. Secret service agents rush to protect the president. President Reagan has been shot!

Present Day – Moscow

A young man visits the home of former KGB officer, Viktor Petrovich (Jon Voight). 30 years ago, Petrovich studied everything about Reagan, from his younger years as a football player, lifeguard and radio reporter to his career as a movie star and eventual rise to the highest office in America. Petrovich educates the young man about the major historical happenings during the Cold War, many of which he witnessed firsthand, and how the “Crusader” (Reagan) brought about the downfall of the Soviet Union.

Which wouldn’t have happened if the assassin’s bullet had proven fatal to the newly-elected president. Coincidence or providence?

Before I dive into such provocative questions in my analysis of the new biopic, Reagan, I need to issue a disclaimer: while I always try to be fair and balanced in my reviews, my objectivity may be compromised in this instance since I esteem Reagan as the finest president of my lifetime.

That said, the story, written by Howard Klausner, is reverent in its portrayal of the 40th President of the United States, but feels rushed at times…perhaps because Reagan accomplished so much during his extraordinary life. However, while focusing on Reagan’s more heroic qualities, Klausner breezes past such negative events as the Iran-Contra scandal and disingenuously suggests that Reagan’s bout with Alzheimer’s disease didn’t become pronounced until after he was out of office (in reality, Reagan’s Alzheimer’s became progressively worse during the latter stages of his presidency).

Though Klausner checks all the boxes of the noteworthy events and achievements in Reagan’s life, he only gives us a few glimpses of the actual person. These include quiet moments when Reagan shares his self-doubts with wife Nancy (Penelope Ann Miller) or when he takes time out of his busy schedule to compose handwritten notes to a world leader or a young boy whose goldfish died. But these scenes only give us a quick peek behind the curtain at the real person, while the balance of the picture is enamored of the historical figure. In short, Klausner’s inability to humanize a very human man is a significant shank.

Unfortunately, the film’s directing is also a miss. Sean McNamara (The Miracle Season) is adequate to the task, but the story of such a beloved American president deserved more than just adequate treatment. With its lengthy establishing shots of city skylines and punchy score that tries too hard to infuse slower scenes with energy, the movie often feels like a glorified TV mini-series. Still, the movie is an admirable effort since it didn’t have the financial backing of a major Hollywood studio.

If the film has a strong suit, it’s the cast. Quaid is the movie. If his portrayal had fallen flat, the film would’ve too. Though he isn’t a dead ringer for the president, Quaid’s speech and mannerisms approximate Reagan’s without drifting into caricature. Also, Quaid pulls off Reagan’s twinkle in the eye charm with comparative ease.

The transformation of Quaid to look like Reagan over the decades is remarkable, so kudos to the makeup department for pulling off one of the most realistic aging processes I’ve ever seen in a film (of course, it helps that Quaid is in amazing shape for his age).

It’s ironic that Quaid’s star was rising in Hollywood during the same years Reagan was president. Now, Quaid is playing the famed president at age 70 (Reagan was 69 when he took office).

In another casting coup, Voight is absolutely superb as Petrovich. His Russian accent is credible and his performance is skillfully understated. Instead of being bitter and angry over losing to Reagan, Petrovich has developed respect, perhaps even admiration, for the American president. Why else would Petrovich devote so much of his life to studying Reagan’s exploits? Profiling Reagan, from his early years to his golden years, is more than a job…it’s an obsession. All of this is conveyed through Voight’s masterful performance without a single line of dialog to explain Petrovich’s psychology.

Though many of the supporting actors don’t have prominent parts, they make the most of their allotted screen time. The eclectic collection of journeyman performers includes: Mena Suvari, C. Thomas Howell, Amanda Righetti, Kevin Dillon, Xander Berkeley, Lesley-Anne Down, Robert Davi, Mark Moses and many others. In a pair of blink-and-you’ll-miss-‘em cameos, Kevin Sorbo plays Reverend Ben Cleaver, Reagan’s childhood pastor, and Pat Boone plays Reverend George Otis, the man who predicted (or prophesied?) that Reagan would become president.

Spoiler warning: some may find it odd that the story of one the most highly regarded American presidents is told by a Russian. This narrative device is certainly compelling from an artistic perspective, but how will audiences (largely conservative, one would assume) react to this more liberal story choice? Perhaps I’m making a mountain out of a molehill, but time will tell.

In a medium that’s typically hostile toward religion, it’s refreshing to see faith foregrounded, and positively portrayed, in a modern movie. In addition to glimpses of corporate worship and scripture reading, several people are baptized in a local river in one scene.

From the early stages of the film, we’re shown how church attendance and participation was a significant part of Reagan’s life. Even as a young boy, Reagan recited Bible passages from memory (a skill that would later help him learn lines as an actor and memorize speeches as the president) in front of the congregation of the First Christian Church of Dixon, IL. It’s also encouraging that young Reagan sought advice from Reverend Cleaver, who, by many accounts, became like a second father to the boy.

It’s plain to see how such a strong moral upbringing paid dividends in Reagan’s adult life, especially when he was faced with ethical and existential challenges as commander-in-chief. While his record reflects many successes, it wasn’t spotless. The Iran-Contra affair remains a black mark on his presidency. As if exploiting a loophole to sell arms to Iran in order to fund the Contras in Nicaragua wasn’t bad enough, Reagan lied about it when questioned by the press. Later, when the word “impeachment” was being tossed around by many politicians on Capitol Hill, Reagan apologized for lying to the American people in a national TV address. Though he eventually made the right decision, Reagan shouldn’t have allowed things to escalate before coming clean to the public.

The result of this admission of failure was that, by and large, the American people forgave Reagan his transgression. When recounting the event, Petrovich tells his young protégé, with a hint of amusement, that the American people “forgive you every time.”

Even before getting into politics, Reagan’s life was marked by hardship. Aside from growing up with an alcoholic father, life dealt Reagan a haymaker when a child he conceived with his first wife, actress Jane Wyman (Suvari), died on the day she was born. Soon after that tragic event, the couple was divorced.

In the wake of the divorce, a dispirited Reagan tells his mother (Jennifer O’Neill) he “missed the boat on that whole purpose thing.” This exposes the danger of tying our purpose in life to a spouse or career. Reagan’s mother admonishes him to “remember who you are and who you serve.” These wise words help Reagan reevaluate his life and career.

A short time later, Reagan met his second wife, Nancy (Miller). When Reagan tells Nancy he’s divorced, she graciously replies, “We’re all damaged goods.” Feeling the weight of his purpose, Reagan tells Nancy, “I just want to do something good in this world…make a difference.” Nancy’s reply is her commitment to stand by his side: “[That’s] hard to do alone.”

Another devastating blow came in 1976, when Reagan lost the Republican party nomination to Gerald Ford. Reagan accepted the loss as part of God’s will, but it also was a matter of timing. Whereas the nation could’ve benefited from Reagan’s leadership in the late 70’s, it was desperate for his guidance and moral clarity in the 80s. In retrospect, Reagan was the right leader during one of the most dangerous periods in our nation’s history.

Of course, the most harrowing moment of Reagan’s presidency was the assassination attempt by mentally ill gunman, John Hinckley Jr. This brings us back to the question posed above: was Reagan’s life spared by God or was it just fate? From the proximity of the bullet to Reagan’s vital organs, there can be little doubt that it was a miracle he survived the shooting (especially at his age). During his convalescence, Reagan said everything happens for a reason and that the shooting was “part of the divine plan” for his life. It could be said that Reagan’s brush with death served to solidify his purpose and fuel his tireless fight for freedom during his presidency. And, some would argue, that the hand of providence was on Reagan, and the nation, during his time in office.

In the end, this movie is about a man who loved God, his country, his wife and his horses. It isn’t overly complicated, but then again, neither was President Reagan. Compared to today’s Machiavellian and morally murky politicians, Reagan was a straight shooter. Perhaps that’s why he’s so well-loved.

Reagan is a very timely movie, not only because of the upcoming election, but also because of the recent failed assassination attempt on President Trump’s life. The two presidents share more than this unfortunate distinction. Many of Trump’s policies were taken directly from Reagan’s playbook. Both presidents focused on freedom, faith and family rather than petty politics, personal power grabs and polarizing propaganda, as did many of their political adversaries. Also, they believed in a stronger, freer, more prosperous and more moral (though certainly not perfect) America. That’s just as much (if not more so) Reagan’s lasting legacy as it is Trump’s.

As opposed to the “odor of mendacity” that permeates the current administration, the optimism inherent in Reagan’s administration was a refreshing breath of liberty, but also a sobering reminder that, as he once stated, “Freedom is never more than one generation away from extinction.”

Tip: Be sure to stay through the end credits—if the actual footage of Reagan’s funeral and archival photos of various moments of his life aren’t enough to move you, the closing letter is sure to leave you misty-eyed.

Rating: 3 out of 4

Deadpool & Wolverine (R)

28/08/24 23:57

Starring: Ryan Reynolds

July 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

“Is nothing sacred anymore?”

That saying is extremely relevant to the proceedings in the third Deadpool movie, Deadpool & Wolverine.

As crass and crude as the previous two films were (and they were…to a superlative degree), D&W plunges us into new depths of degradation. We’ve become so desensitized to violence (at least since the advent of 80s action flicks) that we just keep laughing during the movie’s multiple splatter-fests, especially the graphic visuals of soldiers having their skull and spine ripped from the rest of their body (video games are complicit here too) or when a man is reduced to a pile of blood and entrails. Worse still, one character describes, in explicit detail, how he’ll kill his enemy and have sex with the corpse.

Have we become ISIS?

Was the debauchery and thirst for bloodshed in ancient Rome any more pervasive, any more pernicious, than what’s evident in our society today?

But we keep coming back for more. Which allows the studios—regardless of whether it’s 20th Century Fox or Marvel (some of the best jokes in the movie involve the studio swap)—to finance future films containing even more detestable language and lewd, crude and socially unacceptable behavior. And so the downward spiral goes until we eventually lose our country (a la Rome), and more importantly…our souls.

So, why do we continue watching such grisly, graphic and gratuitous movies (that, in turn, produce deranged citizens)? Because the guy in the red suit is really charismatic, and really funny; he’s less a superhero than a stand-up comic (but one that would make George Carlin blush). Another reason is that the overblown, uber-gory fight scenes appeal to our inner barbarian. These sequences recall the brutality of the Roman gladiatorial games, Medieval tournaments, Old West showdowns, gangster-era shootouts, and Asian blood sports; all haunting reminders of our savage past.

Question: do these murderous melees help exorcise our inner demons (by providing a cathartic release when our heroes slaughter an army of enemies) or unleash them (by reinforcing evil desires that can lead to aggressive or heinous behaviors)? If the nightly news is any indication, the answer is definitely the latter.

And then there’s the off-kilter stories in these Deadpool movies, which are essentially loose associations of plot ideas held together by humorous dialog and heavily-choreographed action sequences. The story in D&W is one step above abysmal. It’s fitting that a movie so filled with filthy language and raunchy dialog would spend a significant portion of its screen time in a trashed-out realm that contains allusions to Mad Max (ramshackle motorcade) and Star Wars: Episode VII – The Force Awakens (half buried ships protruding from the desert sand).

Once inside the enemy fortress, which is built out of a gigantic Ant-Man suit, we’re introduced to Cassandra Nova (Emma Corrin, who was exceptional in A Murder at the End of the World). She claims to be Charles Xavier’s sister, but looks like his granddaughter. Normally, the villain is the most over-the-top character in an action movie, but here, Cassandra is the most constrained and realistic person in the film (other than Wolverine—Hugh Jackman is eternally reliable as the gruff, laconic adamantium-man).

Sadly, Corrin’s talents are wasted on a second-rate story that dispenses with her character before we even get to know her. Also wasted are the cameos of Wesley Snipes and Jennifer Garner, who reprise their roles as Blade and Elektra, respectively. However, the scenes with Chris Evans boast a really nice twist and represent the only hint of writing acumen in the entire film.

The most underserved character in D&W is Wolverine. He doesn’t show up until about 30 minutes into the movie and merely serves as the straight man to Deadpool’s flamboyant (all aspects of the word) funny man. The titular characters become embroiled in not one, but two fight scenes. These conflicts are utterly meaningless other than to fill up the screen time with more action beats to help gloss over the fact that there’s very little story here.

Ironically, the finest aspect of the film is its self-reflexive comments about how awful Marvel’s multiverse movies have been. The inference is that this movie is the exception…it isn’t. Also, anyone who hasn’t watched Loki on Disney+ might be thoroughly confused when the TVA agents arrive and attempt, but fail, to inject some narrative complexity into the listless story.

In the final analysis, D&W is morally reprehensible in every way imaginable (and in many ways you couldn’t possibly imagine before subjecting your brain to the movie’s rancid and putrid subject matter). With dialog that flows like sewage on tap, D&W is crass, rank and vile for the sake of being crass, rank and vile. Aiming at being controversial, irreverent and vulgar, the movie tosses three bull’s-eyes.

Much to our detriment and shame, D&W represents the high art of our crooked and depraved generation. It has glorified and normalized every form of sin, including vicious bloodletting and necrophilia.

In a time when evil is called good and we’ve become so enamored with the vain and profane, D&W’s steady diet of dung tastes like a five course meal from a five-star chef.

But don’t be fooled…that brown liquid flowing from the fondue fountain isn’t chocolate.

Rating: 1 out of 4

Twisters (PG-13)

22/08/24 23:06

Starring: Daisy Edgar-Jones

July 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

Avid storm chaser, Kate Cooper (Daisy Edgar-Jones), leads a team of fellow enthusiasts in a coordinated effort to dissipate a twister by releasing chemicals inside the swirling cloud of debris. When her experiment goes awry, the team frantically flees the raging tornado on foot, but only Kate survives the tragic run-in with nature’s fury funnel.

Five years later, Kate is working in the weather department of a major news outlet in New York City. One day an old friend, Javi (Anthony Ramos), pays her a visit. Javi entices her to return to Oklahoma, which is experiencing a record summer for tornadoes. Still haunted by her earlier failure, Kate only agrees to a one-week excursion because newer technology might aid her research and help validate her experiment—which has the potential to save millions of lives.

What ensues is a series of close encounters with the titular terrors.

In case the name of the movie wasn’t a dead giveaway, yes, Twisters is a loose sequel to Twister (1996). I say “loose” because none of the characters or actors from the earlier film appear here. In fact, the only direct reference to the original film is the sensor-dispensing bucket, named Dorothy V (Dorothy I-IV were deployed by the weather wizards in the first film).

That isn’t to say the films have nothing in common. On the contrary, both movies take place in Oklahoma and spotlight rival groups of storm chasers; Kate’s chief competitor, Tyler (Glen Powell), is a cocky social media star who seems more concerned with sensationalism than science. Also, both films feature a number of deadly tornadoes and show the wreckage left behind in their wakes, i.e., demolished crops, farms and small towns (including a drive-in theater in Twister and brick-and-mortar cinema in Twisters).

Another area of connective tissue between these movies is how both heroines were traumatized by tornadoes in the past. This psychological scarring causes both Dr. Jo Harding (Helen Hunt) and Kate to become obsessed with the awesome power of twisters. There’s a clever allusion to Moby-Dick here; Jo and Kate are stand-ins for Captain Ahab and the twisters they chase are their version of the white whale (indeed, the inciting incidents that trigger their persistent perilous pursuits are when the whale chomps off Ahab’s leg and the tornado wounds Kate’s leg). Unlike Ahab, however, Jo and Kate create experiments to help them better understand tornadoes and give individuals in harm’s way advanced notice of an approaching twister. In other words, Ahab turned his pain into revenge, while Jo (who lost her father to a tornado) and Kate (who lost three friends to a tornado) turn their pain into purpose.

Kate exhibits a sixth sense about the movements of tornadoes. This is a trait she shares with Bill Harding (Bill Paxton) from Twister. In similar scenes, both Bill and Kate step away from the main group of characters to scrutinize the storm clouds on the horizon (Bill tests the direction of the wind by releasing a handful of dirt into the air; Kate does the same with a handful of dandelion seeds).

Where the films diverge is in their casts and story elements. Hunt and Paxton were established movie stars when they made Twisters, but Edgar-Jones (Where the Crawdads Sing) and Powell (Top Gun: Maverick) are hardly household names. Also, the supporting team members here are far less colorful and memorable than those in Twister (especially Philip Seymour Hoffman and Alan Ruck as “Rabbit”).

In a story dominated by heart-stopping chases, multiple scrapes with death and maximum destruction, there’s little time for characters to stop and reflect on the deeper meaning of life. Still, despite its furiously-paced plot, the movie does explore a few meaningful themes. Sadly, none of them are as weighty as the one that hovers like an angry thundercloud over Twister—namely, divorce.

Twister begins with Bill serving divorce papers to Jo (which would never happen in real life) and Jo finding every excuse in the book not to sign the documents. Bill gets swept up into chasing storms with his old crew and discovers he has far more in common with Jo than his new, prim and proper fiancée (Jami Gertz). At the end of the movie, Bill and Jo kiss and appear to be well on their way toward rekindling their marriage.

Interestingly, another disaster movie from the same year, Independence Day, includes a subplot where a divorced couple, David Levinson (Jeff Goldblum) and Constance Spano (Margaret Colin), is reunited after the devastating alien attack. At the end of the movie, they embrace and seem to be back together as a couple.

These two movies represent a rare, and brief, trend in modern movie history where Hollywood offered positive examples of couples pushing through hard times and giving their relationships another shot.

An ancillary topic in Twisters, that avoids being whisked away by drilling its augers deep into the action-centric plot, is greed. An unscrupulous businessman swoops in after a town has been leveled by a tornado and offers to purchase the property from people who’ve lost everything—in essence, making a profit off the misery of others. When given the choice between lending aid to the citizens of a town ravaged by a twister or making shady deals, one of his employees says, “I don’t care about the people.” Those whose sole focus is financial gain will surely lose in the end, because, as the saying goes, “You can’t take it with you.”

Though the entire story revolves around characters chasing tornadoes, woven into the fabric of the movie’s subtext is the more meaningful matter of what the characters are really chasing in life. Early in the movie, Kate chases a grant that will allow her to attend a prestigious meteorological program. Later, she chases her dream of saving lives by “choking tornadoes.” At the beginning of the movie, Tyler is chasing fame and thrills. Later, once he comes to see what’s really important, he chases Kate. Javi chases a career where he makes really good money helping people, or so he thinks. Javi’s boss and righthand man are chasing money…at all costs.

So, what’s the point? Everyone is chasing something. The question is, are we chasing things that serve self or others?

Ironically, some people’s evil ambitions are more dangerous than chasing a tornado.

One area where the new film has a clear advantage over the original is in the visual effects department. Granted, the FX in Twister were excellent for the time, but they can’t compete with today’s CGI. The technology in Twisters is also a quantum leap ahead of what was used in Twister: crude computer graphics displayed on bulky laptop screens have been replaced by high-definition digital images projected on 4K monitors. The coolest piece of new tech in Twisters is the drone that’s in the shape of a small plane—the images it captures as it approaches a tornado are breathtaking.

In honor of the original film, Twisters was shot on Kodak 35mm film to capture the rich colors of the various Oklahoma locations. This is a really nice touch that helps unify the overall look and feel of both movies.

Some may criticize Twisters for hewing too close to the OG film. However, though occasionally paying homage to the 90s disaster film, this is an original story that makes a concerted effort to cut its own path. And, other than its fits of foul language, Twisters is fairly clean and will appeal to a broad audience.

Though Twisters probably won’t win any awards for writing or acting, it is entertaining. And, at the end of the day, that’s all most people who go to see this movie will care about.

So, is Twisters as good as Twister? No, but it’s a pulse-pounding popcorn flick with a serviceable plot and some really good visual effects. Though admittedly influenced by its heavy dose of nostalgia, Twisters was the most fun I’ve had at the cineplex in quite some time.

It remains to be seen whether or not this movie will blow away audiences, but if a sequel is in the offing, I’ll see you at Twisters 2—a surefire winner over at Rotten Tornadoes.

Rating: 2 ½ out of 4

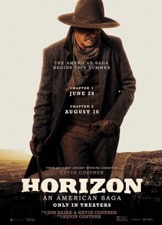

Horizon: An American Saga - Chapter 1 (R)

11/07/24 23:24

Starring: Kevin Costner

June 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

1859

San Pedro Valley

Some Caucasian settlers mark off property boundaries near a river. Two indigenous boys assume the strange behaviors are part of a game.

Sometime later, an old man rides up to the river and finds the dead bodies of the settlers. He buries them and moves on.

Montana Territory

A woman shoots a man with a rifle, puts a baby in her carriage, and rides away.

Back at the first location, an Apache war party burns down a village that’s sprung up near the river, brutally killing men, women and children. Only a handful of people survive.

Wyoming Territory

A man arrives in a mining town and immediately finds trouble when he befriends a local prostitute, who unwittingly maneuvers him into a deadly shootout.

And on and on the story goes…meandering like one of the movie’s many rivers.

From this scattershot synopsis of Kevin Costner’s Horizon: An American Saga – Chapter 1, you’ve probably guessed that the story is a loose association of Western vignettes, some of which eventually merge, while others remain standalone subplots. Costner, who served as actor, director, co-writer and producer on the movie, sunk $38 million of his own money into this passion project. The first of a planned four-movie series, Horizon returns the renowned Yellowstone actor to familiar terrain (Silverado, Dances with Wolves, Wyatt Earp) and is the first Western film he’s directed since the truly fine range war drama Open Range (2003).

When standing behind the camera, Costner’s goal was to match the quality of the Westerns from Hollywood’s classical period…a tall order. He adopts many elements from Golden Era films (continuity editing, cause and effect storytelling and “invisible style” framing) for his character scenes. By contrast, Costner employs many modern cinematic techniques (swish pans, quick cutting and handheld camera filming) for the movie’s handful of fight scenes. While the film’s locations are absolutely spectacular, my preference would’ve been for Costner to let the vista shots “breathe” a little more (like the many exquisite prairie shots in Dances with Wolves) instead of immediately cutting back to the characters. But maybe he was trying to trim action where he could due to the movie’s interminable length.

Costner’s performance, as drifter Hayes Ellison, is typically understated and typically solid. Joining Costner onscreen is a panoply of veteran stars and character actors. Sam Worthington (Avatar) is particularly good as the leader of a cavalry troop. While Michael Rooker (The Walking Dead) delivers a fine performance as a cavalry soldier, his thick Irish brogue makes it difficult to understand what he’s saying. Sienna Miller (American Sniper) and Jena Malone (Sucker Punch) make the most of their limited parts. Other familiar faces pepper the cast, like Will Patton, Tim Guinee, Danny Huston, and Giovanni Ribisi. For my money, the two best performances in the movie come from Luke Wilson, who plays the unelected leader of a wagon train who’s just trying to keep the peace, and Abbey Lee, who portrays Mary, the duplicitous prostitute who selects Hayes as her mark.

With so many superlative aspects of the film, why such a low rating? It’s all about the story, or lack thereof. The script, written by Costner, Jon Baird and Mark Kasdan, is deficient on nearly every level. Simply put, if you like movies with intricate plots, finely-crafted dialog and at least a little levity, Horizon isn’t for you. (Also, if you have bladder issues, Horizon definitely isn’t for you.)

Despite scant character development, we’re just expected to join Costner on his joyless journey into a ferocious frontier. Problem is, we barely get to know one set of characters before he shifts focus to another group of characters, and so on. When the Apaches attack the settlers, we’re sorry that they’re slaughtered, but we have no emotional investment in the characters since we just met them and know nothing about them.

Compounding this issue, we’re often dropped into the middle of a scene with characters we don’t know. By the time we kinda’ figure out what’s going on, we jump to another storyline. Rinse and repeat. It was literally halfway through the film (when Mary decides to leave with Hayes) when I first felt some forward momentum in the plot.

The strangest aspect of Horizon is that it ends with a dialog-free montage of clips from future movies in the series. This stunt reminded me of the preview of Back to the Future Part III at the end of Back to the Future Part II. But here, there isn’t any on-screen text or a voice-over narration to explain what’s happening. The movie ends with Ribisi peering out a shop window with a look of bewilderment on his face. After investing three hours in this substandard jaunt into the Old West, we know exactly how he feels.

Though faith was a significant part of most people’s lives during this period of American history, Horizon is extremely dismissive in the way it treats religion; it presents Judaism, Catholicism and Christianity as relics from the past, dead and buried in the sin-stained wilderness. Sure, we occasionally encounter a Christian symbol, like the cross that stubbornly stands atop the only remaining wall of a dilapidated mission, or when a man buries a trio of bodies and places three wooden crosses above their graves, but that’s about the extent of anything overtly religious in the movie.

The only direct reference to the Bible is when a woman reads from Psalm 23 right before she ignites a keg of gunpowder and sends everyone (her family and the encroaching Apaches) in the immediate vicinity to kingdom come. Ironically, she doesn’t adhere to the very scripture she quotes, which admonishes her to “fear no evil.”

If Costner’s goal with Horizon was to portray the true history of the American West for modern audiences and future generations, he’s failed miserably. His version of the Old West is replete with bitter, vile and unsavory characters who lack even basic morality, with nary a God-fearing soul to be found in the rascal-ridden realm.

We’re taken inside several bars and brothels, but does Costner’s camera cross the threshold of a church? Nope. The movie has plenty of bullets, but does it have any Bibles? Nope. One of the main characters is a prostitute, but is there a priest among the cast? Nope.

In short, Costner’s Hollywood-ized, revisionist history of the American West eschews accurate portrayals of faith and family in favor of all manner of wanton acts committed by vain, profane and lecherous individuals. Even protagonist Hayes’ actions are far from heroic. It’s frightening to think that many impressionable young people who see this film will accept it an accurate account of the Old West.

The hymn “Amazing Grace” is sung (rather poorly) over the end credits. This seems like a makeup call for a movie that grossly underrepresents the beliefs of the era it seeks to depict.

In the end, Horizon is an exceedingly barbaric, yet terminally boring, tale that comes complete with cardboard characterizations, confusing crosscutting, unexplained time jumps and a jarring montage at the end of the film.

On the plus side, Costner’s historical epic is well-acted and beautifully filmed. However, it’s marred by shallow character development and a threadbare plot. So, what’s the end result of all these elements? Horizon is the greatest Western live-action cartoon ever made. Indeed, you’d be hard pressed to find a more pedestrian, less enjoyable Western than Costner’s clunker.

And the really bad news…with three more three-hour Costner pics in the works, there appears to be no relief on the horizon.

Rating: 2 out of 4

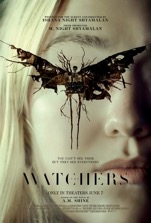

The Watchers (PG-13)

11/07/24 23:23

Starring: Dakota Fanning

June 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

Mina (Dakota Fanning) is a bored pet store employee who prefers vaping and doodling in her sketchbook to doing actual work. Her boss asks her to deliver a golden parakeet to a nearby town in Ireland. She reluctantly agrees, probably figuring a drive through the country would be preferable to staring at lizards and snakes all day. Most people would question their GPS when finding themselves on a single-track dirt road in the middle of a dense forest, but not Mina.

When her car dies, Mina strolls into the forest to find help, but immediately gets lost. As night approaches, she encounters Madeline (Olwen Fouéré), an old woman who tells her to get inside a concrete bunker before vicious creatures (Watchers) come out to hunt. Once safely inside the large rectangular room, Mina meets the other survivors, Ciara (Georgina Campbell) and Daniel (Oliver Finnegan). They mindlessly recite the rules as if in a trance: don’t open the door after dark, don’t turn your back on the mirror, don’t go near the burrows (giant holes in the ground), etc.

During the day, the four survivors go outside to hunt for small game, collect medicinal herbs and venture out as far as they dare in every direction to make a map of the region…but they must always return by sundown. One night, there’s a banging at the door. It’s Ciara’s husband John (Alistair Brammer), who’s been missing for several days. His urgent cries for help are soon drowned out by the shrieking howls of the rapidly approaching Watchers.

Should they risk letting him in?

This is just one of several really good suspense scenes in the lost-in-the-woods thriller The Watchers, which marks the directorial debut of Ishana Shyamalan, daughter of M. Night Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense). Ishana also wrote the script, which is based on the book of the same name by A.M. Shine.

The movie starts out well with an intriguing mystery, restrictive rules and compelling iconography (especially the “Point of no return” signs), all set in an immersive, eerie environment. Unfortunately, the story fails to capitalize on its strong premise by relying too heavily on horror movie gimmicks, which really aren’t that scary.

In addition to mimicking other horror films, The Watchers infuses a heavy quotation of The Time Machine (1960) into its narrative. In that film, based on H.G. Wells’ seminal sci-fi tale, the surface-dwelling Eloi must retreat indoors before dark or risk being eaten by the cave-dwelling Morlocks. In The Watchers, the titular creatures live deep underground and access the surface through large burrows in the ground. Similarly, in The Time Machine, characters access Morlock caves by entering cone-like openings on the surface and climbing down a long ladder. Not exactly the same, but close enough for the sake of comparison.

The whole bit with delivering the bird, the scenes where flocks of birds fly overhead, and the action beat where a bird dive-bombs one of Mina’s friends, are all reminiscent of the gags used in Alfred Hitchcock’s The Birds. Also, there’s an allusion to the hatch in Lost, but I’m not going down that rabbit hole.

To its detriment, the movie is riddled with nitpicks and plot holes. Spoilers: for instance, what happens to all the cars left behind by those who get lost in the woods? Does the forest just swallow them up (that seems to be the case with Mina’s car)? Also, during their many months spent in confinement, no one thought to look under the rug; and it’s only when the Watchers are banging down the door that they discover the hatch? C’mon! And would you really trust a pet store parakeet to guide you through the woods to a lake? Grade A ridiculousness. And then there’s the most egregious plot blunder; Madeline should’ve insisted on being the one to collect the documents from the professor’s office since she previously had a relationship with him. Though Mina learning about the origins of the Watchers helps keep the audience up to speed, it reveals the truth the Watchers have kept secret for centuries. Shoddy plotting.

Another downside is that the third act keeps stringing us along but never delivers the “Aha!” moment we’ve been anticipating since the start of the film. Perhaps Ishana was leery of employing a climactic twist since that story device proved to be such a fickle feature of her father’s films. Probably a wise precaution since a poorly-executed surprise ending could’ve tanked an already middling movie.

On the plus side, Ishana makes the most of her locations; the film was shot entirely in Ireland. It isn’t much of a stretch to say the creepy forest serves as an additional character in the film. In a very real sense, the hair-raising atmosphere is more dynamic than many of the characters, which have all the charm of the terrified trees that shiver each time a Watcher crawls past them in the dead of night.

But enough about the movie’s production elements. Let’s take a look at the film’s socio-political aspects...

Before I saw The Watchers, I jotted down some general thoughts about the movie’s most striking image: four people trapped inside a glass-walled room surrounded by a foreboding forest at night.

Symbolically, the image may represent our…

- Fear of the surveillance state. Pervasive paranoia from always being watched. The government listening in on our phone conversations—the Patriot Act. TVs Person of Interest.

- Fear of the weaponization of governmental agencies. People jailed over the Jan. 6th riot, some of whom weren’t even in D.C. that day. The IRS targeting conservative groups (Lois Lerner). FBI labeling parents at school board meetings as “domestic terrorists” and targeting “radical-traditionalist Catholics.”

- Fear of the loss of personal privacy. Identity theft. Prevalence of social media…everything we post is searchable. We can be cancelled for what we say/believe. May make us feel like we’re living in a glass house…like animals in a zoo.

- Fear of another lockdown. People trapped inside their homes. Loss of the freedom to go about their normal daily lives. Physically shut off from other people.

Of all the potential plot points listed above, the movie only addresses the “animals in a zoo” element (one character thinks the whole thing is a test, that the Watchers are observing them to see “what can drive a person mad”). It’s a shame that the movie chooses hokey pseudo-mythology over cultural relevance; signs and symbols (the blatantly obvious analogy of the bird in the cage and the four people inside the bunker) over substance. Any meaning derived from the movie is done so by accident rather than by design (i.e., is Mina’s apartment number “2B”—as in “to be or not to be”—a knowing nod at her existential crisis, or am I way ahead of the director…or just plain off my rocker?).

The movie does pose an interesting, unspoken question though, “Who watches the Watchers?” The answer is: the audience. We’re watching the Watchers watch their captives. This fascinating meta perspective underscores the notion that all film spectatorship is voyeuristic by nature. Hitchcock explored this theme from various angles in such movies as Psycho, Vertigo and Rear Window. I suppose if Ishana had to borrow from someone it might as well have been from the master of suspense (sorry pops).

In another meta level subplot, Mina and the others watch old episodes of a reality series called Lair of Love (a made-up series in the mold of Big Brother) on DVD. Lair follows a dozen people around an isolated house and focuses on their frequent romantic escapades. Unlike the TV show, there are only four people shut into the bunker in the movie and, fortunately, none of them fall in love with each other.

Indeed, there’s very little love in The Watchers (and, sadly, very little to love). By contrast, there’s a palpable, almost oppressive, feeling of evil in the film. This feeling is accompanied by many depictions of evil, like the winged skeleton made out of bones and sticks that sits atop a warning sign and the drawings/paintings of shadowy or tall, pale creatures in books or wall paintings in a professor’s office. The physical manifestations of evil in the movie are the Watchers themselves, which come in different shapes, sizes and temperaments (indeed, the movie never properly classifies the mythical beings, referring to them as fairies, changelings, winged people, and halflings—send royalty checks to the Shire, Middle Earth).

Halflings are the result of a Watcher male mating with a human female. According to the movie, in the distant past Watchers and humans lived in harmony, some more so than others, it would seem. Though this story point sounds kind of out there, it does have literary precedent: gods (most notably Zeus) mated with human women in Greek mythology, and spiritual beings mated with human women in the Bible—producing giant humans known as the Nephilim. The movie eschews a thorough explanation of Watcher/human relations in favor of the supposedly shocking revelation that halflings are living among us. Big deal! The newer Battlestar Galactica did that with Cylons, to far better effect.

The Watchers squanders solid directing and decent acting with contrived and derivative story elements including a muddled faux-mythology. Other than a few meaningful character moments and a couple good scares, the story doesn’t really accomplish anything.

In the end, it’s unfortunate that Padawan Shyamalan spent too much time thinking about the Watchers on the screen and not enough time thinking about the watchers in the theater.

Rating: 2 out of 4

Unsung Hero (PG)

22/05/24 22:44

Starring: Daisy Betts

April 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

David Smallbone (Joel Smallbone), an Australian music promoter, has had some success in bringing contemporary Christian bands from America to the land Down Under in the late 80s. Despite sound advice to the contrary, David turns down a “lesser act,” DeGarmo & Key, and signs a major deal to bring over emerging superstar Amy Grant for an extensive concert tour.

Then the nation suffers an economic downturn, resulting in Grant performing for crowds of hundreds rather than thousands. Since David’s name appears on the contract, he ends up losing his job and foreclosing on his beautiful home.

In an act of desperation, David takes a job in America and moves his wife, Helen (Daisy Betts), and six kids (with one in the oven) to Nashville, TN. Showing up to work on the first day, David learns that his position was given to someone else. Since his work visa prohibits him from getting another job, David resorts to doing landscaping work for cash with his older kids just to afford their unfurnished house. When David solicits work at a nearby mansion, guess who opens the door? Yep, you guessed it…Eddie DeGarmo!

Right off the bat, the movie gives us a poignant lesson in the dangers of pride. David considered it beneath him to bring DeGarmo’s band over to his country. Now he’s in DeGarmo’s country scrubbing his toilet bowl. How the mighty have fallen.

Pride rears its ugly head when David is shamed by generous neighbors and fellow churchgoers. He pushes them away right when his family needs them most, when child #7 arrives. David’s inability to find a job and provide for his family sends him into a state of debilitating depression.

In yet another act of pride, David shuns the advice of his loving father, James (Terry O’Quinn). During a phone conversation, David hangs up on his dad; an act that comes back to haunt him just days later when James unexpectedly dies.

Of course, this film isn’t about debased David, his long-suffering wife or his ever-encouraging dad, it’s about the Smallbone children—three of whom would grow up to become Grammy Award-winning performers.

They say kids are resilient, and this movie certainly proves that aphorism true. Without beds, batteries for toy robots or even much to eat (Ramen again?), the kids found ways to stay busy helping the family and somehow managed to have fun despite their limited means and humble circumstances. This spotlights the movie’s main theme, which is that the most important things in life are faith and family—an ethic exemplified by the Smallbone clan.

The most famous Smallbone is the eldest daughter, Rebecca St. James (Kirrilee Berger). Her younger brothers, Joel and Luke, are members of the group For King & Country. In an ironic feat of casting, Joel (who also co-wrote and co-directed the film) plays his father, who was about his age during the early 90s, when the movie is set.

There are many highlights in the film, including the two-hanky Christmas scene when neighbors show up with everything on the Smallbone’s wish list; furniture, washer and dryer, Christmas tree and presents.

The movie’s culminating moment comes when seventeen-year-old Rebecca auditions for DeGarmo, with her younger brothers singing background vocals (the tryout comes complete with edited home video footage projected onto a large screen by another of the Smallbone boys). Rebecca’s original song, “You Make Everything Beautiful,” has a lilting quality and a catchy, hum-all-day melody.

So, who’s the titular agency? Is it the unidentified benefactor who pays the Smallbone’s hospital bill after the birth of their youngest child? Or is it some unseen guiding hand that, through all their hardships, has been leading the Smallbone family to exactly where they need to be? Depends on what, or who, you believe. But there’s no mystery as to what the Smallbone family believes.

Unsung Hero is an inspirational, follow-your-dreams biopic that reminds us of the power of courage, kindness and perseverance.

And to honor God, country, family and all the other heroes in our lives.

Rating: 2 ½ out of 4

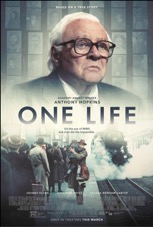

One Life (PG)

03/04/24 23:21

Starring: Anthony Hopkins

March 2024

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

One Life chronicles the extraordinary true story of Nicholas “Nicky” Winton (Johnny Flynn), a young stockbroker at a London bank, who rescued hundreds of children from the streets Prague on the eve of World War II.

From a young age, Nicky’s mother, Babette “Babi” Winton (Helena Bonham Carter), instilled in him a desire to help those in need. This “If you see a need, lend a hand” mentality compelled Nicky to help the refugees in Prague. All told, his efforts led to the rescue of 669 children who were transported on eight trains—a ninth train, with over 200 children aboard, never arrived because Hitler’s invasion of Poland ignited World War II. The children from the failed mission, many of whom ended up in concentration camps, weighed heavily on Nicky’s conscience for the rest of his life.

Nicky’s nagging melancholia over the people he wasn’t able to save mirrors the titular character’s plight in Schindler’s List (1993). In a haunting scene at the end of that film, Oskar Schindler (Liam Neeson) laments the fact that he could’ve rescued more people; he calculates how many more lives could’ve been saved had he sold his watch and car. Despite the crushing weight of underachievement, both men secured a lasting legacy, namely the descendants of the people (largely Jewish) they saved.

Fifty years after the rescue effort, old Nicky (Anthony Hopkins) reflects on his earlier exploits, which are dramatized in a series of flashbacks. Nicky’s wife Grete (Lena Olin), tells him it’s time to let go of the past. While she’s away on a trip, Nicky drags dozens of file boxes from his study to the front yard, where he turns the mound of historical documents into a bonfire (an ironic twist on Nazi book burning).

The one item from the past Nicky just can’t bring himself to part with is a leather briefcase that contains a scrapbook of all the children he helped rescue. Nicky presents the scrapbook to a local London newspaper, but a decades-old account of Jewish children being rescued from another country fails to pique the editor’s interest.

When Nicky meets with a museum director, she says the scrapbook is too important for her collection, but asks if she can borrow it. That decision creates a chain of events that brings Nicky face-to-face with his legacy.