2020

Tenet (PG-13)

31/12/20 20:09

Starring: John David Washington

September 2020

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. Views are my own and elaborate on comments that were originally tweeted in real time from the back row of a movie theater @BackRoweReviews. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

“To the degree that it’s not plot, any experimental structure will call attention to itself and often seem visibly artificial. So it has to be managed carefully or the story, the human content, will become secondary to the style. The story may even disappear altogether, lost in the clever externals of its presentation. One of the most damning things that can be said about a story is that it’s an amazing technical achievement.”

Those words come from Ansen Dibell’s Plot. Ironically, that writing resource was published in 1988, five years before CGI took a giant T-Rex leap forward in Jurassic Park (1993). How many CG era films does that “style over substance” indictment describe? A staggering number, I think (I’m looking at you Star Wars prequels).

The first thing that popped into my mind while reading Dibell’s quote was director Christopher Nolan’s Dunkirk (2017). Nolan’s depiction of the eponymous WWII debacle was a visual marvel, yet featured some of the scantiest character development in cinema history. You can read what an epic fail Dunkirk’s story was in my review.

So here we have Tenet, Nolan’s follow-up to Dunkirk. Nolan’s fascination with time (Memento and Interstellar) and the nature of reality (Inception) collide in Tenet. Sadly, Tenet resembles Dunkirk more than those earlier Nolan successes.

Tenet is a rare exception where the trailer is better than the movie. The preview establishes a time-bending reality where generically-named Protagonist (John David Washington) and Neil (Robert Pattinson) experience effect before cause. This causal reversal creates some startling visuals, particularly when we see a crashed car flip over and drive backward through freeway traffic.

However, for all its “amazing technical achievements,” Tenet is clearly missing what the Tin Man yearned for in The Wizard of Oz (1939)…a heart. Lack of heart also was the narrative Achilles’ heel of Dunkirk, which starred Kenneth Branagh (who plays villain Andrei Sator here).

Since Tenet’s sole writing credit belongs to Nolan, the movie’s dearth of genuine human moments has exposed his storytelling inadequacies; in the past, Nolan’s stories were buttressed by the superlative efforts of David S. Goyer and his brother, Jonathan. Nolan fails to reveal significant personal details about any of his characters. Without a connection to the characters, we aren’t really concerned for their safety—the same was true of the cardboard cutouts that populated Dunkirk.

Despite its intriguing premise, Tenet is a wholly uninvolving and unmoving tale due to its shallow characterizations and uninspired performances. Sad to say, but this decorated, scintillating cast is grossly underserved by Nolan’s script. Pattinson is flat, Branagh is unconvincing (especially his beard), Washington is unreasonably overconfident, and Michael Caine and Martin Donovan are mere blips on the radar (which, like tenet, is a palindrome).

Then there’s the question of where the movie’s MacGuffins come from—namely, objects that cause time to flow backwards. Are the artifacts alien in origin? The reference of “somewhere in the future” is egregiously vague (more lazy screenwriting). Also, Sator’s scheme to destroy the world is right out of a 70s James Bond movie. Nothing original here.

Though brilliantly realized, the action sequences actually undermine the film. For example, when we see a fight scene staged backwards earlier in the story, do we really need to see the same sequence played forwards later in the movie? We get the point already.

Worse still, two earlier sequences are revisited later in the movie—the freeway car chase and the melee at the airport. Returning to the same locations and sets feels like a retread and is an egregious waste of screen time, proof positive of the story’s tenuous construction. These hollow and anticlimactic action scenes may induce the sensation of déjà vu, restlessness from boredom, or both.

To the movie’s credit, it makes the audience work to figure out what’s going on—it’s the opposite of mindless entertainment. Also, the movie boasts a few exceptionally well-crafted action set pieces. These pulse-pounding sequences will leave many viewers completely satisfied, regardless of the flaccid story.

However, despite its ambitious high concept premise, Tenet is too long, too confusing and, surprisingly, too monotonous. In the end, the film is an interesting puzzle for the mind, but it isn’t an enjoyable entertainment.

The sequel, teneT, will be this movie played backwards.

Rating: 3 out of 4

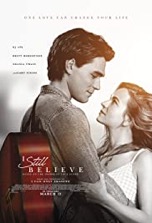

I Still Believe (PG)

22/04/20 22:12

Starring: Britt Robertson

March 2020

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. Views are my own and elaborate on comments that were originally tweeted in real time from the back row of a movie theater @BackRoweReviews. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

Based on the real-life experiences of singer Jeremy Camp, I Still Believe is a unique film in that it’s both heartbreaking and inspiring. That bittersweet dichotomy permeates every moment of this tragic love story, which also focuses on faith and family.

Jeremy Camp (K.J. Apa) and Melissa Henning (Britt Robertson) meet at a concert and it soon becomes apparent that their love is written in the stars. But the universe throws the young couple a curveball when Melissa is diagnosed with cancer.

To its credit, the story doesn’t degenerate into a melodrama when depicting its tragic events. There isn’t a false note during the film’s emotionally gut-wrenching passages, particularly those that take place in the hospital.

The film benefits from some superb acting. Though Apa and Robertson scintillate as the movie’s central couple, the supporting cast is equally impressive. Jeremy’s parents are portrayed by Gary Sinise and Shania Twain. One of Melissa’s sisters is played by Melissa Roxburgh, the star of TVs Manifest. In an ironic bit of casting, Cameron Arnett, who played a terminal patient in last year’s Overcomer, appears here as Melissa’s doctor.

The film is directed by the Erwin Brothers (Andrew and Jon), who also helmed last year’s surprise hit I Can Only Imagine; another biopic about the life of a musician, Bart Millard. In a refreshing gesture of paying it forward, Millard serves as one of this movie’s producers.

The Erwin’s have done an amazing job of making a modestly budgeted film feel like a prestige studio drama. Aerial shots, like the ones at Camp’s beachside concert, are impressive and surely weren’t cheap to film. The movie also boasts a diverse soundtrack and an affecting score by John Debney (The Passion of the Christ).

A two-hanky tearjerker, this film will have added significance for anyone who’s lost someone. It’s an eternally hopeful love story filled with music and more than its fair share of genuine, human moments.

In the end, I Still Believe is a moving true story of true love. It’s anchored by superb performances and features a story unafraid to ask some of the big questions about life…and death. And what it means to really believe.

Rating: 3 out of 4

The Call of the Wild (PG)

09/04/20 22:57

Starring: Harrison Ford

February 2020

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. Views are my own and elaborate on comments that were originally tweeted in real time from the back row of a movie theater @BackRoweReviews. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

Based on the Jack London novel of the same name, The Call of the Wild feels like a Disney movie, but isn’t (the movie was produced by 20th Century Studios).

Harrison Ford cuts a rugged figure as old-timer John Thornton. Ford certainly looks the part; he grew a bushy prospector’s beard in three and a half months. Ford’s performance is predictably strong as a man with vastly different priorities than most of his contemporaries. Unlike everyone else headed “North to Alaska,” Thornton’s goal isn’t gold nuggets, only solitude.

Ford anchors a cast that features oddly checkered acting. Bradley Whitford is solid in his blink-and-you’ll-miss-it part as Buck’s (Terry Notary) former, forbearing owner. Buck’s dogsled masters, played by Omar Sy and Cara Gee, are superb in physically demanding roles. It’s fitting that Sy and Gee’s characters deliver the mail since they deliver strong supporting performances that keep the story zipping along during the film’s early passages.

Ironically, the weakest performance comes from one of the finest actors in the cast…Dan Stevens. The one-note heavy Stevens portrays makes a Disney villain seem complex by comparison. Witness Stevens’ face when he enters Thornton’s cabin. His maniacal mask is so inhumanly contorted that I actually thought the movie had switched to an animated feature for a few beats.

This kind of melodramatic and megalomaniacal part is a tremendous disservice to Stevens, who, in other contexts (Downton Abbey), has proven himself to be a fine actor. Here, he plays a greedy, cruel (especially to animals), unreasonable opportunist who wouldn’t last five minutes out in the wild.

Set in the Yukon in the 1890s, the locations (many of which were filmed in British Colombia and Yukon, Canada) are mind-blowingly frigid (winter) and lush (summer). While director Chris Sanders (How to Train Your Dragon) does a fine job of creating the look and feel of London’s pioneer world, it’s Janusz Kaminski’s (Schindler’s List) cinematography that helps capture the alternatingly breathtaking and terrifying majesty of the Great White North.

The only knock on the visuals is that the saturation is really augmented during the summer sequences and the aurora borealis shots were quite obviously created with CGI. While on the subject, why was it necessary to CG animate Buck, the St. Bernard/Scotch Shepherd mix? Sure, the process of filming a live animal can be a bear (especially when it is one), but there’s just no replacing the genuine article.

Having a human inside a mo-cap suit mimicking the motions of a dog is preposterous (as it must’ve seemed to Ford when he had to pet Notary’s head). Although the final result isn’t embarrassing, there are moments when we can see right through the CG veneer, especially when, in an anthropomorphic display, Buck tosses Thornton a sideways glance. My preference would’ve been for real, rather than mo-cap and CG, animals in the movie. Featuring the latter was a major impediment to my enjoyment of the film.

In the end, The Call of the Wild is a crowd-pleasing retelling of London’s classic adventure yarn. Excellent production values and gorgeous locations greatly add to this family-friendly tale of adventure and companionship between a man and his dog. For better or worse, the movie is exactly what you expect it to be.

So, will you answer the call?

Rating: 2 1/2 out of 4

1917 (R)

06/02/20 21:02

Starring: Dean-Charles Chapman

January 2020

Warning! This is NOT a movie review. This is a critique of the film. Intended to initiate a dialogue, the following analysis explores various aspects of the film and may contain spoilers. Views are my own and elaborate on comments that were originally tweeted in real time from the back row of a movie theater @BackRoweReviews. For concerns over objectionable content, please first refer to one of the many parental movie guide websites. Ratings are based on a four star system. Happy reading!

The movie’s serene opening is completely unexpected…two British soldiers are napping in a field in northern France during the height of WWI. Lance Corporal Blake (Dean-Charles Chapman) is roused by a superior officer and told, “Pick a man. Bring your kit.”

Before Blake’s waking friend, Lance Corporal Schofield (George MacKay), can protest, the two young men are trudging through a winding labyrinth of trenches. After several minutes of maneuvering down narrow passageways, the soldiers finally arrive at General Erinmore’s (Colin Firth) command bunker.

Erinmore wastes no time in outlining Blake and Schofield’s assignment—they are to cross over into enemy territory, rendezvous with a British battalion and deliver a letter which warns of a German trap. Failure to deliver the message will jeopardize 1,600 men, including Blake’s brother. This is one impossible mission even Ethan Hunt wouldn’t accept.

The movie’s premise is simple enough and, barring a few twists along the way, the plot is fairly straightforward too. But story (director Sam Mendes and Krysty Wilson-Cairns wrote the screenplay) isn’t the movie’s strong suit. Even though the film features excellent performances from Chapman, MacKay, Firth, Andrew Scott, Mark Strong and Benedict Cumberbatch, acting isn’t its strong suit either. (Fans of BBC’s Sherlock will note that the series’ hero and chief villain are both among this movie’s cast).

So why is 1917 causing such a stir (many top critics have lauded the film and it just won Best Motion Picture at the 2020 Golden Globes)? In short, 1917 is a cinematic achievement. Though that phrase is employed far too frequently these days, it’s wholly justified in this case.

For 1917, Mendes (Skyfall) has attempted the seemingly impossible. Mendes’ original concept, which was inspired by his eight minute sequence at the beginning of Spectre (2015), was to film his WWI epic as a single shot in real time. Alas, unlike TVs 24, the movie doesn’t occur in real time, nor was it shot in order (a few scenes were shot out of sequence). However, the film does achieve the feeling of one long, continuous shot.

This certainly isn’t the first war movie to employ uber-difficult long takes. Many will point to the frenetic, bone-jarring long take in Stanley Kubrick’s Paths of Glory (1957)—where Kirk Douglas leads his men on a writhing, weaving course along a bomb-blasted battlefield—as the finest of its kind. Others could make a strong case for the extraordinary long takes in The Longest Day (1962), Atonement (2007) and, of course, Saving Private Ryan (1998). While those films featured one significant long take each, 1917 is comprised of a series of extended takes, the longest of which is nine minutes. There’s no overstating the magnitude of what Mendes and cinematographer Roger Deakins (along with the alchemic editing team) have achieved here.

The film took extensive planning and execution to pull off. The sets were constructed in an almost storyboard fashion. The movie proceeded scene by scene, station to station, and through trenches, mud pits and tunnels. If it rained, the company shut down (but continued to rehearse) until the weather cleared. Conversely, if the previous scene was shot under an overcast sky and the sun peaked through the clouds, they had to wait for the sun to go back in. The sheer logistics of producing such a project (constructing 5,200 feet of trenches, filming in the mud and elements for 65 days, etc.) are mind-boggling and exhausting to consider.

Most war movies contain similar themes, such as bravery, courage, sacrifice and friendship. Blake and Schofield exhibit excellent teamwork as they work in tandem to overcome the many obstacles thrown in their path. Their training is evident and their dedication to the mission is admirable.

At one point, Schofield asks Blake why he was chosen for the mission. Blake asks Schofield if he wants to go back. Schofield proves his loyalty as a friend and fellow soldier by remaining at Blake’s side.

This degree of loyalty and companionship is reminiscent of Frodo and Sam’s in The Lord of the Rings trilogy. Similar to Blake and Schofield’s trek, the Hobbits are required to traverse inhospitable regions filled with untold dangers in order to accomplish their objective. At one point, Schofield tries to pick up Blake, just like Sam did with Frodo. As sidekicks, both Sam and Schofield are willing to sacrifice themselves for their friend.

There are many unforgettable visual compositions in the movie. In one scene, a crashing German plane rapidly approaches Blake and Schofield from behind as they run straight toward the camera. The shot recalls Cary Grant sprinting away from the low-flying crop duster in North by Northwest (1959).

In another scene, Schofield exchanges fire with a German sniper and ends up falling down a flight of stairs. After an undetermined span of time (brilliantly, the film fades to black for a few moments), Schofield finally regains consciousness.

Despite its unqualified brilliance, the movie surely will have its naysayers. Some may feel the movie’s progressive plot and filming technique have detracted from the overall viewing experience while simultaneously distracting many from realizing that the cause and effect story could’ve been written by a 10-year-old (with all due deference to today’s savvy young people). Others may criticize the movie for being enamored with its own style. All are valid arguments. Normally I grade down for “style over substance” spectacles (like Dunkirk), but 1917 is a landmark effort that deserves nothing less than top marks.

In the final analysis, Mendes has achieved a staggering feat of cinematic wizardry with his ambitious one-shot filming. The movie is bolstered by stunning cinematography, astounding production elements, a beautifully restrained score by Thomas Newman and superb performances from its cornucopia of a cast. 1917 is an immersive, visceral and unrelenting journey through claustrophobic trenches, sodden plains and hellish landscapes…with cat-sized rodents and corpses to spare.

1917 is an unparalleled cinematic achievement unlikely to be outdone in our lifetime. Above all, 1917 has pushed the art forward. Regardless of its many accolades, that will be its lasting legacy.

Rating: 4 out of 4