The Chronicles of Narnia: The Voyage of the Dawn Treader (PG)

Starring: Ben Barnes

December 2010

“Third Journey to Narnia Fails to Showcase the Book’s Unbridled Creativity”

I know I’m not alone in my conviction that the third book in C.S. Lewis’ Chronicles of Narnia series, The Voyage of the Dawn Treader, is the finest in the seven book fantasy cycle. I temper my less than flattering comments about the movie adaptation of Lewis’ novel, directed by Michael Apted (Amazing Grace), with the knowledge that my expectations of the film were, admittedly, far too lofty. That said, Dawn Treader is a remarkably, inexplicably un-magical journey into Lewis’ enchanted realm. Although each book bursts with charm and imagination, it can be argued that Dawn Treader represents a high watermark for Lewis, who had clearly hit his creative stride at this point in the Narnia series.

Opinions may vary as to what went wrong with the movie, but for my money the film suffers from a tension between narrative polarities; the story hews too closely to the original source material in some instances and takes too many liberties with original story details and structure in others. Most noticeable to viewers who’ve read the book is the movie’s juggling act with major events in the story—the encounter with the Dufflepuds comes much earlier and Eustace’s (the perfectly cast Will Poulter) transformation into a dragon comes much later in the film version. The natural byproduct of this scrambled structure, besides overriding the author’s original intentions for the story, is an uneven narrative that feels more like choppy waters than smooth sailing.

While the Dufflepuds, disappointingly, only appear for about two minutes in the film (the single element I most wanted to see in the movie), Eustace, who remains a dragon much longer in the film version, factors more significantly into the story’s climax. Although some story alterations work better than others (Good: collecting the seven swords from the seven lords, Bad: a thought-generated sea serpent that looks like it was borrowed from the Pirates of the Caribbean franchise), such embellishments, like the extraneous It’s a Wonderful Life styled scene with Edmund (Skandar Keynes), Peter (William Moseley) and Susan (Anna Popplewell), weren’t the movie’s biggest creative liability. Ultimately, what draws the Dawn Treader off course, as ironic as it sounds, is pacing. Apted and company bring so much admiration and zeal to the project that their enthusiasm creates the narrative equivalent of a runaway train. And we all know the demise of runaway trains.

So, now that the Narnia books featuring the Pevensie children have found their way to the big screen, will we see the final four books in Lewis’ series (which largely exclude the Pevensie’s) adapted for the big screen? I supposed the better question is whether or not this effort has warranted the production of future films in the series. Unlike the hugely successful Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings fantasy franchises, the quality of the Narnia film series has decreased with each new release.

As such, it now seems doubtful that The Silver Chair, The Horse and His Boy, The Magician’s Nephew or The Last Battle will ever be translated into motion pictures. As for The Horse and His Boy, whether or not we ever get to see it realized as a feature film, at least we have Albert Lamorisse’s brilliant White Mane (1953) to fill that cinematic niche. Though only forty minutes in length, Lamorisse’s touching tale of a special and sacrificial friendship between a boy and his horse has more magic than Dawn Treader has in its entirety. Worth a watch!

Rating: 2 1/2

The Ghost Writer (PG-13)

Starring: Ewan McGregor

March 2010

“Polanski’s Political Potboiler Stars a Superspy and a Jedi”

Roman Polanski’s The Ghost Writer, though not as shocking as Chinatown or as haunting as The Pianist, is a fine film in its own right, a taut thriller told from the epicenter of a political earthquake. At the center of the epicenter is Adam Lang (Pierce Brosnan), former Prime Minister of Britain, who’s been accused of advancing American policies while he was in office. The revolving door of ghost writers commissioned to massage Lang’s memoir into printable form soon sweeps a young and ambitious scribe, simply referred to as The Ghost (Ewan McGregor), into the web of intrigue and controversy that seems to surround Lang wherever he goes: Lang ping-pongs back and forth between native England and the eastern seaboard of the US.

We enter Lang’s world as an interloper, a voyeuristic onlooker to the drama that unfolds around Lang and those in his orbit. Lang, though understandably and undeniably aristocratic in public, is much more subdued behind closed doors, especially in one-on-one interviews with The Ghost. Past the officious exterior, Lang, when finally able to lay aside the worries of the world, displays a degree of vulnerability that’s a bit unsettling at first. It’s an expertly measured performance by Brosnan, a career actor with an inestimable range (Lang is a light-year from Bond).

McGregor also turns in a fine performance that’s deceptively understated in its fly-on-the-wall subtlety. Even though Lang is sympathetic and central to the plot, the audience identifies more strongly with The Ghost since he’s brought into the political turmoil at the same time that we are. As The Ghost forms his opinions of Lang, we’re right there peeking over his shoulder, sensing, as he does, that something isn’t quite right in Lang’s world.

The Ghost’s expressions of confusion, suspicion and apprehension are mirrored on our faces: in this way, director and writers see to it that character and audience are on equal footing. Or perhaps Polanski is deluding the audience into a state of false confidence. Perhaps The Ghost is one step ahead of us and the only reason we’re clued in at all is because his writer’s eye is leading our gaze to details we would normally miss. Either way, this narrative choice allows for tangible tension to reign supreme throughout the story…and we can be grateful in our consternation since the movie’s intricate web of intrigue ensures a more satisfying viewing experience than a paint-by-numbers puzzler.

Of course, keeping the audience in the dark and methodically parsing out plot details at a pace which produces maximum suspense is a staple of the thriller genre, and few do modern-day political potboilers better than Polanski. Polanski knows how to gradually build anticipation until…bang, some major character revelation or unforeseen event causes a rupture in the story’s stasis. Even though the action never reaches the fevered pitch of a Bourne movie, there are some nail-biting episodes like when The Ghost takes a trip on a ferry boat and discovers that he’s being shadowed.

Though the film’s intensity ebbs and flows (like the undulating ocean waves visible through the window in Lang’s office), an undercurrent of dread is ubiquitous, like apprehensions over the impending storm. The literal storm that’s been brewing since the movie’s early stages finally hits midway through, just as several character arcs are reaching their breaking points. The storm scene, of course, is symbolic of what the characters are experiencing. What would’ve come across as telegraphed by a lesser director is artistically and organically achieved by Polanski, whose expert grasp of storytelling allows for a slow boil approach to these climactic events.

The movie’s East Coast locales serve as an additional, though non-corporeal, member of the cast. The visual splendor Polanski creates, with the assistance of cinematographer Pawel Edelman, is nearly palpable. The overcast, blustery shoreline scenes along Martha’s Vineyard (surprisingly shot in Germany) are visually immersive and are the perfect accompaniment for the movie’s melancholy mood. The scene where McGregor bikes over to Eli Wallach’s house, the expanse of gray and beige creating a haunting yet beautiful tableau all around him, has more atmosphere than many movies have in their entirety.

One of the film’s many highlights is the showdown interview between The Ghost and Paul Emmett (Tom Wilkinson). Few actors can lace pleasantries with napalm like Wilkinson; his character’s thinly veiled disdain for The Ghost boils just beneath the surface of his composed and professional demeanor. Besides containing some tense, hair-raising dialog, the verbal sparring match between Wilkinson and McGregor sets into motion a chain reaction that ultimately leads to The Ghost’s untimely demise: if you’ve seen any of Polanski’s back catalog you can make an educated guess at the nature of the film’s down ending.

Although The Ghost Writer fails to measure up to Polanski’s earlier masterpieces, it’s still a taut yarn with fine performances and a riveting riddle that will keep the audience guessing right up until the bitter end. And let’s face it, a lesser Polanski film is still better than the vast majority of films Hollywood is turning out these days. There’s little intrigue in that statement.

Rating: 3

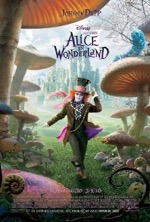

Alice in Wonderland (PG-13)

Starring: Johnny Depp

March 2010

“Burton’s Timing and Creative Vision are Off in Wonderland”

Alice is in the most unenviable position imaginable…she’s at her own engagement party and has a revulsion to her husband-to-be. A crowd has assembled to witness the momentous occasion and, much to Alice’s horror, her homely suitor drops to one knee and pops the question. Feeling the radiant heat of a hundred expectant gazes burning holes into her face, Alice does what any sane person would do—she flees the vicinity; leaving her would-be fiancé and accompanying crowd in a stupefied trance.

While pouting near a hollowed out tree, Alice hears noises from inside the tree and bends over to take a look. The ground gives way and Alice falls, falls, falls down a surreal tunnel filled with obstacles like chairs, pictures and a grand piano. Once through a magical door, Alice finds herself in Wonderland, but after taking one look at the dismal and drab alternate realm, I’m sure the blonde debutante is prepared to accept her fate and take her chances topside with rodent boy.

And so begins Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland (2010), based on Lewis Carroll’s children’s masterpieces Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, which is utterly uninteresting, as incredulous as that sounds. Despite its surfeit of vision, Wonderland is disappointingly bereft of heart. Johnny Depp’s performance as the walleyed Mad Hatter is unsettlingly askew, though not nearly as creepy as his portrayal of Willy Wonka in Burton’s other film about the chocolate factory. Helena Bonham Carter’s turn as the Red Queen is serviceable though not nearly as blood-chilling as it could or should have been. Newcomer Mia Wasikowska is acceptable as Alice, but Ann Hathaway is horrendous as the White Queen: Hathaway tries too hard to appear regal and glides along with her hands in the air as if in a perpetual waltz.

However, what debilitates this iteration of Wonderland isn’t the acting or directing or even the sometimes bearable other times insufferable special effects, but that most capricious of commodities…timing. If Wonderland had been released six months ago it would’ve blended in seamlessly with the concurrent sci-fi/fantasy films and Burton would’ve received well-deserved kudos for yet another frenetic and fantastical fiat of fractured-reality filmmaking. As things stand, Wonderland is the first in what is certain to be a long succession of CGI films that will fail to measure up to James Cameron’s Avatar (2009) and will be harshly, perhaps unfairly in some instances, judged for their technological shortcomings. When compared to Avatar’s special effects, Wonderland’s CGI is like a secondhand account of a rumor based on yesterday’s news. That is to say, due to the painfully obvious disparity in CGI quality between both films, Wonderland looks like it predates Avatar by at least a year even though it’s the newer film.

In reality, it might be a while, perhaps a year or more, before the average effects picture reaches the technological proficiency achieved by Avatar. Armed with that knowledge, why did Burton opt for a mixture of live action and CG characters instead of an all-out F/X film? Burton’s choice, in twenty-twenty retrospect, would appear to be ill-advised since the resultant mixture of live-action and CGI is strangely uneven and ineffably odd, but not the kind of odd you’d normally associate with Carroll’s classic or Burton’s oft-deranged sensibilities.

The full-on CGI rendering of The Cheshire Cat (voiced by Stephen Fry) works quite nicely in the film, especially when the teleporting feline de- and re-materializes with enough frequency to give spectators a mild whiplash. In contrast, the bulbous heads of the Red Queen, Tweedledee and Tweedledum (Matt Lucas), which look like they were achieved by shooting into one of those silly carnival mirrors, are bizarre even by Burton’s standards. One wonders if Cameron’s mocap wouldn’t have been a better option for the queen and her two tweedles.

Borrowing from Carroll’s “Jabberwocky” poem in Through the Looking-Glass, Alice, in order to fulfill a prophecy, must slay the dreaded Jabberwocky…which turns out to be your standard-issue dragon. The Jabberwocky (voiced with the appropriate degree of malevolence by Christopher Lee) appears to be a repainted and rescaled version of the barely adequate fire-breather at the end of Enchanted, another fantasy-themed Disney film released in 2007. Instead of looking to Enchanted for inspiration, Burton’s F/X team should’ve used the impressively rendered dragon in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire (2005) as their touchstone. Believe me, when I say the Jabberwocky is a sorry excuse for a dragon I’m not just blowing smoke.

The climactic battle between the Red Queen’s life-size metallic playing card soldiers and the White Queen’s chess piece army is conspicuously brief for a presumably epic confrontation and is frequently upstaged by Alice’s crenellation-hopping duel with the Jabberwocky. The battle, which is visually interesting only because it takes place on a gigantic chessboard, tries to recreate the feverish, pulse-pounding, armor-clanging melees which were executed with preponderant verve, artistry and lyricism in The Lord of the Rings trilogy, but ends up looking like a cheap knockoff of a Chronicles of Narnia film. Ultimately, the final confrontation’s brevity is a blessing in disguise…the CG veneer is stripped bare long before the Hatter launches into his inane victory jig.

The three fantasy franchises referenced above (Rings, Potter and Narnia) clearly illustrate another instance of Wonderland’s poor timing. Though fantasy films have managed to retain their commercial viability over the past decade, genre conventions and iconography have been so well-established by now that all but the most superlative examples of the form are exposed as reheated epics or, worse still, derivative remakes. Having borrowed so liberally from other fantasy series’, Wonderland comes off as routine and safe…like most adapted screenplays in Hollywood these days.

So where’s the wonder in this Wonderland? The curiosity? The levity? Burton’s conception of the titular destination, perhaps not surprisingly, is a dystopian wasteland—a post-apocalyptic acid trip that stands in stark opposition to Carroll’s whimsical, joyful fantasy land. In light of the current global recession, Burton’s timing would seem to be off yet again: right now we need ennobling, encouraging, reassuring fare not yet another bleak and vapid depiction of fractured identities in the postmodern era. It’s too bad Burton didn’t listen to his White Rabbit: the frenzied, furry fellow was trying to tell him all along that he was too late.

Rating: 2 1/2